Nineteen days after the year in question came to an end, I finally complete my list for 2009. Not particularly timely, I know, but here are my final three nevertheless. And although this list was never in any particular order, I do consider these three things to be my favourite discoveries of 2009. So without further ado…

T F POWYS – FABLES

The only book by T F Powys that’s widely available these days is Mr. Weston’s Good Wine, which I’ve yet to read but am really looking forward to laying my hands on some time in 2010. Two others, Unclay and Kindness In A Corner, have been reprinted by small publisher The Sundial Press, but for Fables you need to look in second hand bookshops (I got my copy from an online one for a pittance, and the good news is it was easy to find).

It seems that Powys may be one of those forgotten gems of English literature: too elusive in style to fit happily among his contemporaries, too reclusive in lifestyle to counteract that. Fables was published in 1929, but eighty years later it felt to me potent and fresh. But I should explain more. Theodore Francis Powys lived and worked in the tiny Dorset village of East Chaldon (population today, one hundred and sixty six), where from what I can tell he kept his head down and reflected on the nature of life and religion through the means of his writing. Evidently he was a very spiritual man who would have termed himself a Christian, but his take on religion seems to have been unconventional at least. That’s about all I can tell you about him specifically, other than pointing you at an article by John Gray in the New Statesman, but you can pick up a lot of Powys’ sombre, pensive character from Fables. This is a collection of twenty short stories, all set in and around the fictional West Country village of Madder. In this locale, everything can talk, and each story has at its heart a dialogue between two such conversationalists. When I say everything, I mean everything. Candles, buckets, the waves of the sea, the spitoon in the inn, the headstones in the church yard, everything can talk. Generally the less human a thing is, the more wisdom it has to impart. And wisdom is something Fables has in abundance, and little gems are given out at regular intervals by the least likely of speakers, alongside opaque messages that are dark and strange.

This book reminds me in a lot of ways of Hans Christian Andersen, whose stories are similarly full of talking objects and sudden moral interludes. Yet Powys is darker, stranger and less studied. Plot isn’t important to Powys, but humour is, which is a good thing given that most of the conversations held in Fables turn ultimately to the nature of mortality. Here’s an extract that seem to me to touch on everything Fables is about, taken from the end of my favourite story in the book, John Pardy and the Waves. You’ll just have to forgive him the bit about the maiden’s breast.

The waves had so much entertained John Pardy by their replies to his questions that he laughed loudly, rolling his body backwards and forwards and showing himself to be very merry.

‘Who would have believed it?’ he called out, ‘that fifteen hundred waves, who have talked with God, should take so great a notice of our little family!’

‘Your counting, Mr. Pardy,’ said the waves, ‘is far from being correct. We are more than you make us. And why should we not take notice of little matters? For all things that are made by God have an interest, and there is nothing so small but that some truth may be found in it.’

‘And look,’ cried John Pardy, ‘there before me is one of you, a green wave rising slowly like the gentle breast of a young maiden when she meets her lover. The wave moves fearlessly, it rises higher and still higher and is coming onwards; now ’tis crowned with white foam, it rushes on, breaks and flows to my feet and is seen no more. Surely that wave has died like a man, and will be no more seen.’

‘You are wrong,’ said the waves, ‘for as soon as it broke and was gone, it became one with the vast waters of all the oceans. In a few millions of years, perhaps – and what are these years to us? – those drops of water will collect again, rise up, roll on, and break upon the coast of Greenland during a summer night – but no human creature will see them. Even though we waves lie for centuries in the deeps of the waters, so deeply buried that no man could think that we should ever rise, yet as all life must come to the surface again and again, awakening each time from a deep sleep as long as eternity, so we are raised up out of the deeps high above our fellows, to obey the winds, to behold the sky, to fly onwards, moving swiftly, to complete our course, break and sink once more.

‘We, who are waves, know you, who are men, only as another sea, within which every living creature is a little wave that rises for a moment and then breaks and dies. Our great joy comes when we break, yours when you are born, for you have not yet reached that sublime relationship with God which gives the greatest happiness to destruction.’

‘I am interested in what you say,’ said John Pardy, ‘and I have half a mind to join in your revels; but tell me, if I come to you shall I have the same pleasure in destroying others as I am likely to have when I am destroyed myself?’

‘You may sink a ship,’ answered the waves, ‘and with good luck you may become a tidal wave that will drown a city.’

John Pardy walked into the sea.

WILLIAM ELLIOTT WHITMORE – ANIMALS IN THE DARK

I had the good fortune to come across William Elliott Whitmore just in time to see him while he was touring the UK. If you find yourself with a similar opportunity I’d urge you to go and do the same. One critic described him as having ‘more soul than a graveyard’, and that’s spot on. Added to that his live shows are engrossing, not because of any fancy theatrics but because of the weight of emotion he throws behind his music. He’s got several records out, but Animals in the Dark (2009’s) is my favourite, thanks to its blend of subject matter. Old-fashioned protest songs about political corruption share the tracklisting with heartfelt, gut-turning songs about grief and hope. Then of course there is Whitmore’s voice, which has a broken depth to it reminiscent of somebody like Tom Waits.

I wanted to embed a video of a performance of Old Devils he did for KEXP Radio, but embedding is disabled on that one track only. So here’s the link to that, and an embedded version of Hard Times.

You know when you’ve fallen in love with a record when you find its songs soundtracking your own experiences. This record did that for me in 2009, some of its songs acting as a kind of tonic during some squally patches. You can of course listen to Whitmore further at his myspace page. I’d recommend There’s Hope For You and Hell or High Water and… well, I’d recommend the whole album, of course.

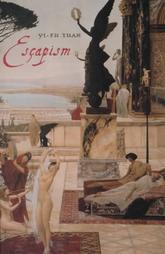

YI-FU TUAN – ESCAPISM

I don’t know where to begin with this one. In a nutshell, this book is a tour-de-force of nigh on every aspect of human experience and society. Yi-Fu Tuan is an emeritus professor and geographer and he has a remarkable ability to take a perspective on human affairs seemingly entirely removed from cultural influences. And that’s a really hard thing to do. Escapism was the last thing I read in 2009 and one of only two books (the other being Fables) that I wanted to start again the moment I finished. Its main theme is that escapism is a human drive that has been fundamental to the development of all our society. Escapism here essentially means the escape from nature, our need to build ourselves protection from the big bad world. Better than any explanation I can give is the blurb posted below, or the Google Books preview, which was what persuaded me to buy the book in the first place. Reading it made me rethink so many things, or simply see them in a new context. I’m more used to reading work by fiction writers or critics who operate in the realms of literature. Contrasted with Tuan’s geographer’s eye, their writings seem incredibly human-centric in a world that firmly is not. That’s fine, but it’s refreshing to see things from Tuan’s perspective.

I have to confess that my brain often clunks out about halfway through most of the more academic books I try to read. The point at which the author, having outlined the basics that underpin their argument, is ready to launch into the real substance of the book is normally the point where I start trailing behind. Yet while I found myself not nearly clever enough to understand everything in Escapism, Tuan’s easily accessible prose style made things far easier on my synapses. It was the most thoughtful, enlightening book I read all year.

I have to confess that my brain often clunks out about halfway through most of the more academic books I try to read. The point at which the author, having outlined the basics that underpin their argument, is ready to launch into the real substance of the book is normally the point where I start trailing behind. Yet while I found myself not nearly clever enough to understand everything in Escapism, Tuan’s easily accessible prose style made things far easier on my synapses. It was the most thoughtful, enlightening book I read all year.

In prehistoric times, our ancestors began building shelters and planting crops in order to escape from nature’s harsh realities. Today, we flee urban dangers for the safer, reconfigured world of suburban lawns and parks. According to geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, people have always sought to escape in one way or another, sometimes foolishly, often creatively and ingeniously. Glass-tower cities, suburbs, shopping malls, Disneyland — all are among the most recent monuments in our efforts to escape the constraints and uncertainties of life — ultimately, those imposed by nature. “What cultural product,” Tuan asks, “is not escape?” In his new book, the capstone of a celebrated career, Tuan shows that escapism is an inescapable component of human thought and culture.

At last, then, I’ve finished my list. It’s been fun to do, but I promise I’ll spare you another one until the end of this year at least . If anyone would like to drop in any recommendations of their own, please do leave them in the comments section.

Thanks for reading.

Ali

A LIST FOR 2009

Rain-Charm for the Duchy by Ted Hughes

The Troll Witch by Mike Mignola

Stornoway at the Sheldonian Theatre

Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy

www.butdoesitfloat.com

The Ooser

District 9 by Neill Blomkamp

Fables by T F Powys

Animals In The Dark by William Elliott Whitmore

Escapism by Yi-Fu Tuan