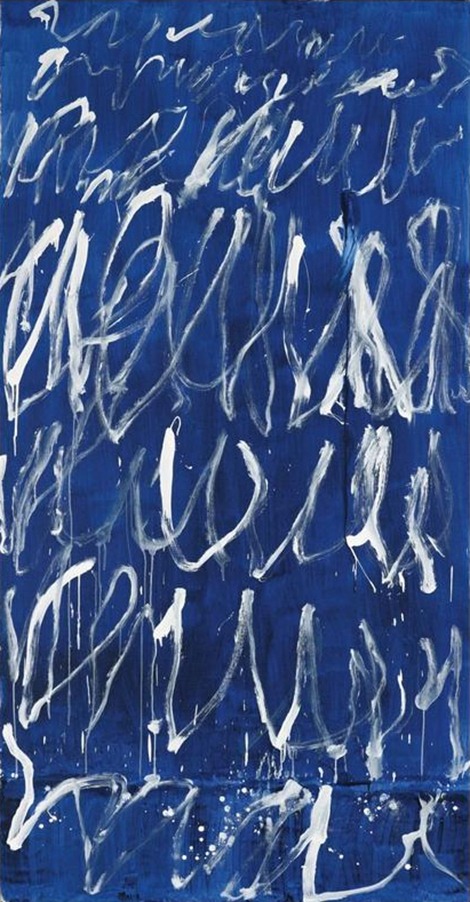

I was sad to hear about the death of Cy Tombly today. In my first year at university, when I was doing fine art, one of the staff noticed that I kept writing on my canvases and suggested that I checked out Twombly, who often incorporated scratchy text into his work. I loved his paintings right away, especially the ones where he scrawled sentences across them, or bits of script that looked like made-up languages, or strange words half concealed behind thicker layers of paint. At a later point, the university art staff suggested that I was writing a little too much on my own canvases, and that perhaps I should be writing on word processors on a different course, but it was worth having been there just for the tip-off about Twombly.

There are good articles about his art in lots of newspapers today, and they will tell you better than I ever could about all the great things he did. Here and here are two I’ve enjoyed looking at. The appeal, for me, is all in a kind of gut recognition. He seemed to understand that the process of a making a mark, be it handwriting or graffiti or frenzied slashing with a palette knife, is as important as the symbolism of the mark itself. In other words, the shape the word is written in says just as much as the word itself.

I was thinking about this a couple of months ago, and that was what I was getting at here. When I got stuck – which was often – writing The Man who Rained, I would think about Twombly’s flourishing scrawls and force myself to forget about structure and narrative and all that rigid stuff and just write, write, not even write but just mark-make, be it real words or made-up words or a made-up momentary alphabet, just to enjoy the feel of the nib moving across the surface of the page. My messy results had nothing of the elegance of Twombly’s – that was the man’s genius, to elevate scribble to a thing of beauty – but they helped me become unstuck and press onward. So thank you, Cy Twombly.

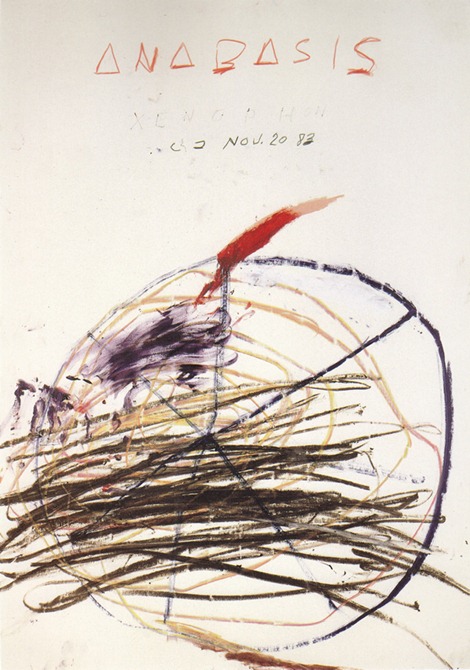

CT: I’m a painter and my whole balance is not having to think about things. So all I think about is painting. It’s the instinct for the placement where all that happens. I don’t have to think about it. So I don’t think of composition; I don’t think of colour here and there. Sometimes I alter something after. So all I could think is the rush. This is in certain things and even up to now, like The Four Seasons, those are pretty emotionally done paintings. And I have a hard time now because I can get mentally ill. I usually have to go to bed for a couple of days. Physically I can’t handle it, and I can’t build myself. You know, my mind goes blank. It’s totally blank. I cannot sit and make an image. I cannot make a picture unless everything is working. It’s like a state.

DS: Like a state. Ecstatic?

CT: Ecstatic, exactly. I’m usually in a very good humour, except that I can be a little violent if it’s going bad. If I’m making a mess I get a little sadistic with the paint, but usually I’m enjoying myself. It’s more like I’m having an experience than making a picture.