The wind was so icy that the frost took a firm grip, but what a sight there was when the sun came up! All the trees and shrubs were covered in rime; it looked like an entire forest of white corals, as if all the branches were heaped with dazzling white flowers. The infinitely numerous and delicate network of branches, which is impossible to see in the summer because of all the leaves, now appeared, every single twig. It was a lacework, and so glittering white, as if a white glow were streaming from every branch.

– from Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snowman

I was some way into writing The Girl with Glass Feet when I rediscovered Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales. By that stage I had done my first rough imaginings of St Hauda’s Land and knew it to be a place full of winter and magic. I remembered being transported to such a land by a picture book of The Snow Queen that I’d owned as a child, so I greedily picked up a copy of Fairy Tales to reacquaint myself. At first I was surprised by how little of that story actually takes place in a world of snow and ice. Much of it takes place surrounded by summery flowers, or in a den full of burning fires and wild robbers. Yet these scenes of heat make the snowy realm of the Snow Queen, when we finally reach it, all the more monochrome and frozen. That’s why, in The Girl with Glass Feet, Ida’s memories and recollections of the mainland are all set in summer. To try to do what Andersen does, making the winter deeper by contrasting it with what has gone before.

Then there is the glass. In the opening chapters of The Snow Queen, a little boy called Kai is struck in the eye and heart by shards of a smashed magic mirror. They turn his heart to a ball of ice and his thoughts cruel and judgemental. In The Girl with Glass Feet, Midas’ father is essentially Kai in adult form – what Kai might have grown into had he not been rescued at the end of The Snow Queen.

My principal debt to Andersen, however, is more abstract. Of all of his stories, the one that had the most impact on me when I reread it as an adult isn’t one of his winter tales. It’s The Little Mermaid.

I don’t really have a beef with Disney about what they did to fairy tales. I’m a big fan of animation in general, and Disney have pioneered it and contributed some charming family films and some brilliant comic shorts during the early days of the studio. Besides, even the Brothers Grimm meddled with their source material to serve social and political ends. All the same their films do tend to invade and occupy the general perception of how a story goes, which I suppose is why I feel the need to mention them here. It does frustrate me that, when I type into Google the name of one of the most staggeringly moving fairy stories, I get this. The Disney version is fine – it has some catchy tunes and a singing lobster who I’m pretty fond of – but essentially it’s an entirely different film about an entirely different mermaid, and perhaps they should have called it something else to avoid the confusion.

Incidentally, if you want to watch a gorgeous mermaid animation I would suggest this by Alexander Petrov.

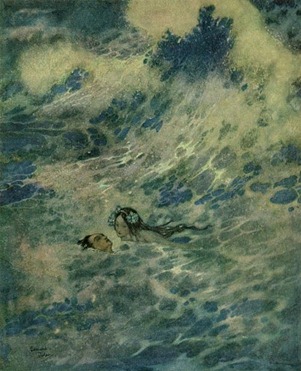

Andersen’s The Little Mermaid is a heart-breaking account of failed love and a perfect example of magic as an expression of emotion. The story has a context you may find interesting: Andersen wrote it after retreating to the island of Fyn to avoid attending the wedding of his friend Edvard Collins. Andersen was in love with Edvard and could neither bear to see him take a wife nor to give voice to the depth of his feelings for him. This is what I mean by magic as an expression of human feeling: the character of the little mermaid can easily be seen as a literary representation of the heartbroken Andersen. To remain in the company of her prince she must endure an agony in her feet that redoubles with every step she takes. To obtain human feet at all she has had to sacrifice her voice so that, like Andersen, she cannot express what she feels for the man she loves.

Then he took her by the hand and led her into the castle. Each step she took, as the witch had warned her, felt as if she were treading on pointed awls and sharp knives, but she gladly endured it. Hand in hand with the prince, she moved as lightly as a bubble, and he and everyone else marveled at her graceful, gliding walk.

– from The Little Mermaid

The Little Mermaid is Andersen’s masterpiece, and from it I drew assurance that although magic should be strange and beautiful, it should not be without cost or pain. Waving a wand (or a trident) and making everything right is not magic, it’s just wish fulfilment. Magic is (and always has been in fairy tales and folk stories) a form of literary expressionism, a way to demonstrate in vibrant imagery the invisible workings of human emotion. I’d fiercely recommend grabbing a copy of Andersen’s fairy tales and rediscovering their strange bittersweetness for yourself.