“Metamorphosis was in the rock of St Hauda’s Land. In quarries, blown apart boulders showed their insides turning to quartz, or revealed fossilised prisoners. The sea gnawed at the coastline, remoulding it with every year. And in nooks and crannies uncatalogued transmogrifications took place…”

– from The Girl with Glass Feet

A lot of readers have asked me about St Hauda’s Land, the little island chain on which The Girl with Glass Feet is set, wondering which real places it’s based on and where it would appear in an atlas if it were not a fictional country. It’s difficult to answer, because St Hauda’s Land developed so gradually. It’s true basis, more than anything, was a pair of glass feet, since everything in the book stemmed from that single image. When I asked myself what kind of landscape glass feet might be found in I knew it would be one covered in snow. The iciness of winter was a perfect match for the crystalline condition of feet turned to glass.

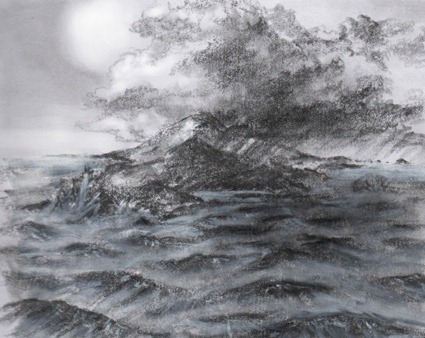

In writing the novel I wanted to explore the idea of feeling like a prisoner to yourself: that your own body and learned behaviour could lock you up when inside you felt you should be free. Just as I wanted Ida’s glass feet to give physical expression to that feeling, I wanted to build a landscape that echoed the idea in every cliff and snow-blasted hill. Hence St Hauda’s Land became a remote chain of island, far from the mainland and caged by a violent sea.

These details gave me my first geographical touchstones in the form of the island territories of the Arctic Circle. I researched the Shetland Isles, Newfoundland and the Faroe Isles, but I never intended St Hauda’s Land to actually be any of those places. Just as the communities living in those locations maintain a fierce sense of their islander identities, I wanted St Hauda’s Land to share certain geographical features while remaining very much its own place. I wanted readers to be able to imagine it in whichever far flung reach of the ocean made the most sense to them.

There was, however, one big problem with the archipelagos of the Arctic. They all missed something that I felt was vital to St Hauda’s Land. Take a look at this lovely video from the national website of the Faroe Islands.

There are no trees. I wanted trees to grow in abundance on St Hauda’s Land because I needed the fairy-tale atmosphere that their cold and twisted trunks could evoke. But as far as I could make out, it was geologically impossible for the kind of woods that birthed the folklore of mainland Europe to grow on volcanic islands such as those mentioned above. Nevertheless I planted them all over St Hauda’s Land, making the place’s existence as physically impossible as a miniature bull with moth wings growing from its back.

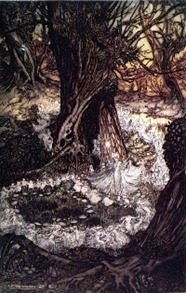

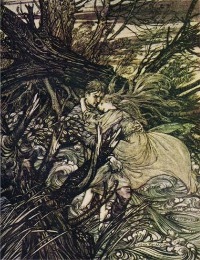

Expressionism has always fascinated me far more than realism, which feels very unreal to me in contrast. Likewise I love this expressive idea of ‘the woods’, by which I mean not the botanical realities of tree species and soil types (interesting though these things can be) but the feelings the woods can instil, the old fears they can stir up in the gloom, the sense when you’re lost that the trees themselves are conspiring against you. The woods help us believe in the impossible (which as an aside is a bloody good reason not to chop them all down) and form a vital backdrop to childhood stories such as those illustrated by Arthur Rackham below. I found myself writing about them from the very first page of the novel onwards, and in my mind they became a kind of communicative apparatus for the islands. I needed these woods of Rackham, the woods of the Brothers Grimm and European folklore, to cast their spell over The Girl with Glass Feet.

Every so often, and usually at the start of each new draft, I scribbled out a map of the islands. This was helpful to keep track of which compass directions characters should head in, how far they could see from each location and so on. The following passage from early in the book was my attempt at a description of the maps I drew.

From an aeroplane the three main islands of the St. Hauda’s Land archipelago looked like the swatted corpse of a blob-eyed insect. The thorax was Gurm Island, all marshland and wooded hills. The neck was a natural aqueduct with weathered arches through which the sea flushed, leading to the eye. That was the towering but drowsy hill of Lomdendol Tor on Lomdendol Island which (local supposition had it) first squirted St. Hauda’s Land into being. The legs were six spurs of rock extending from the south-west coast of Gurm Island, trapping the sea in sandy coves between them. The wings were a wind torn flotilla of uninhabited granite islets in the north. The tail’s sting was the sickle-shaped Ferry Island in the east, the quaint little town of Glamsgallow a drop of poison welling on its tip.

– from The Girl with Glass Feet

I also had a go at sketching the landscapes, with mixed success. Sometimes it helped to build a sense of place, sometimes it just confused it or frustrated me because I couldn’t capture what I was imagining. I had another go recently, but St Hauda’s Land is still difficult to draw. I like to think of it like St Brendan’s Island or Hy-Brazil – eerie islands discovered once by sailors lost in the fog, then never ever found again.

I just finished reading a beautiful book called ‘Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Never Set Foot on and Never Will” by Judith Schalansky. The invented St. Hauda’s Land would fit right in with Schalansky’s interesting list of desolate and inhospitable islands. She says, “Peaceful living is the exception rather than the rule on a small piece of land…” and “It is, however, the most terrible events that have the greatest potential to tell a story, and islands make the perfect setting for them.” How apt!

Thanks Katie – coincidentally, some friends gave me that book for Christmas! I agree that it is wonderful. One of my favourites is the island of Semisopochnoi where, ‘the earth mutters to itself, largely unnoticed by human beings.’