So, as promised and in celebration of La Ragazza dai Piedi di Vetro being available in Italy, here are some pictures for a great folk story collected by the legendary Italo Calvino in his book Italian Folktales. This one is from the same family as The Griffin and The Devil With The Three Golden Hairs (the latter of which in particular is great fun, as are all the stories about the Devil’s long-suffering mother).

Having done some drawings for it, I was unable to find a version of this one on the internet. So, with apologies for my lack of forward planning, I’m afraid you’ll have to make do with the summary version I’ve scribbled below. I’d strongly recommend picking up the proper one in the Calvino book. If you like Calvino’s own fiction these stories are a particularly interesting read, as you get a real sense of how the folk tradition feeds back into his own work.

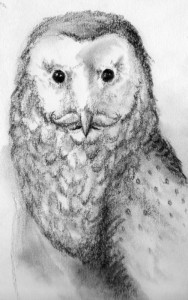

This post will be lengthy enough with the whole of the tale inserted, so I won’t add the ususal musings, I’ll just say that my favourite image from the tale is the final one. It made me wonder whether the feathered ogre has spent the latter part of his life quietly contemplating the decisions he got wrong. Maybe he’s a better person as a result.

If you’re in Italy, La Ragazza dai Piedi di Vetro has a facebook group here.

When a king falls gravely ill his doctors advise him that the only way to recover is to consume a magic feather from the legendary feathered ogre. The king asks his subjects who will be brave enough to set forth and pluck a feather from this man-eating monster, but at the very thought of such a journey his lords and knights fall silent. Only a humble servant steps forward, the only man brave or foolish enough to venture to the ogre’s mountain.

It takes the servant four days to reach the feathered ogre’s lair. On the first night he stays at an inn whose landlord is grieving for his long lost daughter. The landlord asks the servant to bring him back a feather from the ogre, in the hope its magic might restore his daughter to him.

On the second night of his journey the servant stays at the house of two noblemen whose fortunes have dried up. They explain that a fountain in their courtyard once overflowed with molten silver and gold, and that this was the source of their wealth. But the fountain has long since dried up, leaving the noblemen poor. They beg the servant to bring them back a feather from the ogre, in the hope its magic might make the fountain flow anew.

On the third night the servant shelters in a monastery. The friars there are miserable to a man. They explain that for years they have been fighting among themselves, and as such have had no time to do the Lord’s work. They ask the servant to bring them back a feather, in the hope its magic might set aside their differences.

On his fourth day travelling, the servant arrives at the mountain, but finds it to be surrounded by a deep and dark moat. Moored to the bank is a rickety rowing boat, in which an even more rickety ferryman sits huddled. The servant asks what the toll is for passage across the waters. A curse, explains the ferryman, binds him to the rowing boat, and all that he asks for in payment is that the servant – should he survive his trip up the mountain – finds out from the ogre how the curse can be broken.

So after crossing the water and climbing the steep paths to the mountain top, the servant at last arrives at the house of the feathered ogre. There he knocks on the door and is surprised to find it answered not by a man-eating monster but by a young woman. She explains that she is the ogre’s wife and that the ogre is out hunting. If the servant has any sense he will escape while he still has a chance.

But the servant is either brave or a fool, and besides is rather taken with the ogre’s young wife. Realising that she won’t get rid of him easily, she asks what brings him all the way up here. He explains everything, and she agrees to help him on two conditions. Firstly, that once she’s done so he in turn helps her escape the mountain. Secondly, that he stays hidden beneath the ogre’s bed and doesn’t interfere as she pulls the feathers from the ogre’s hide: he might have guts in coming here, but he’s nowhere near as smart as a feathered ogre.

No sooner has she hidden the servant beneath the bed than the door slams open and the feathered ogre stalks in. He sniffs the air and declares that he can smell man-flesh. All you can smell, explains the young woman calmly, is the man-flesh in the stew I’ve been getting ready for you. And lo-and-behold, there on the stove is a saucepan full of the ogre’s favourite treats: man-legs and smoked man-ribs. He slurps up the stew in one go, licks the pan clean, then contentedly climbs into bed. His wife slips in beside him.

As soon as the ogre is sound asleep, his wife chooses a fine feather from his hide and plucks it. The ogre wakes up with a pained squeal, shouting that a feather has been pulled from his skin. Nonsense, soothes the young woman, you were just mixed up in a nightmare. You were talking in your sleep as you dreamed: about some monastery where the friars fight among themselves and have no time for the Lord’s work. Ah, says the ogre, I must have been thinking of an actual monastery I know, down in the lands in the shadow of this mountain. The friars there fight each other because the Devil has taken the shape of one of them. He spends his every hour setting the friars against each other, but if they only all started doing good deeds they would discover the Devil in their midst, for he cannot perform good works.

After that the ogre dozes back to sleep. The wife plucks another feather and again the monster wakes with a yowl. You must have been dreaming again. This time you were sleep-talking about two noblemen whose magic fountain has stopped flowing with gold and silver. Ahh, says the ogre, I must have been thinking about some actual noblemen I know, down in the lands in the shadow of this mountain. They don’t realise that a giant snake has dragged a stone ball into the spring beneath the fountain. If they only smashed the serpent’s head in with the ball, the fountain would flow with precious metals again.

The ogre passes back to sleep, and at once the young woman yanks free another feather. The ogre screeches until the walls shake, but his wife calmly explains that again he has been dreaming, about a ferryman cursed to his rowing boat, and an innkeeper grieving for the loss of his daughter. Ahhh, purrs the ogre, the ferryman needs only to hand his oar to his passenger before his rowing boat touches the shore, and then his curse will shift to the poor fool who accepts it. As for the innkeeper, I must have been dreaming of your idiot father, for you are none other than the daughter he grieves for.

Even in the face of this revelation, the woman keeps her cool. The ogre is by now so exhausted that he drops into the deepest of sleeps, too deep to notice as his wife and the servant escape the lair and flee down the mountain. When they reach the ferryman, the old man asks eagerly whether they have learned how to cure his curse. Wait until we’re ashore, they tell him, and then we’ll explain everything.

They’re good to their word, then hurry on their way out of the shadow of the mountain. When they come to the monastery they inform the friars that they have to start doing good deeds to expel the devil from among them. Then they make haste to the house of the noblemen and tell them to crush flat the head of the snake who lurks beneath their fountain. At last they come to the house of the innkeeper, who is overjoyed to see his daughter again.

Of course, by now the servant and the ogre’s wife are madly in love, and no sooner have they taken the king his magic feather than they ask for his blessing over their marriage. He throws them the most magnificent of weddings, and as far as we know they are still happy together.

As for the ogre, the morning after the couple’s escape, he woke up and realised everything that had happened the night before. In a rage he charged down the mountainside and insisted that the ferryman row him across the dark moat. But the old man’s rickety arms couldn’t work fast enough for the ogre, and he snarled and demanded that he row faster. If, said the ferryman, that’s really what you want, why don’t you take the oar from me? With such big strong limbs, you’ll surely row at twice the speed I can.

The monster snatched the oar from the ferryman, who promptly dived into the water and swam to his freedom. The feathered ogre was cursed to take on the role of the ferryman, and he rows there still.