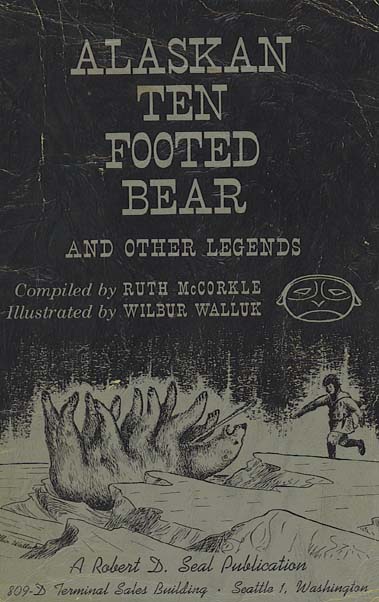

January 1st 1909. Ten-Footed Bear. Tarak told us Wednesday evening that the tenfooted bear lives mostly in the water like a seal. Looks like a polar bear all but the ten legs. When he walks on ice the five feet of each side track after each other so the bear makes a double track like a sled. Walking the bear often gets his legs tangled up; there are so many, he can’t manage them all. Once a man was followed by a ten-footed bear. The man walked between two cakes of ice and the bear was caught in the crevice between them. If his feet had not become entangled he might have gotten off. As it was, the man speared him. When dying, the bear fell on his back, all his feet pawing the air. This is an old men’s story. Tarak never saw such a bear or tracks.

– Vilhjalmur Stefansson, in his Stefansson-Anderson expedition journal, 1908-1912

One of the wonderful things about monsters is that you can make them even more monstrous by merging them together. Many fabulous beasts are a fusion of animal body parts, or of multiple instances of the same creature crammed together: one body with three heads or nine tails. So too the qupqugiaq of the Arctic, who the Inuit and Inupiat peoples describe as a massive polar bear with ten legs. During blizzards, the qupqugiaq rolls onto its back and waves all its limbs in the air. Fooled by the swirling snow, the unwary hunter mistakes the moving legs for a human crowd and goes to them. Then the qupqugiaq tears him into more than ten pieces, and feasts well.

We don’t know much more than that about qupqugiaqs (most of those who survive an encounter only do so by killing the bear), although it would be wrong to think of them as malignant creatures just because they like to snack on human beings. That’s just bears being bears. Evidently the ten-legged polar bear can be an aid as well as a danger. In Explorations in Anthropology and Theology, by Frank A. Salamone and Walter R. Adams, the authors’ Inupiat host describes how his son inherited a ten-legged bear as an animal helper (a feral kind of guardian angel) from an ancestor. ‘Polar bear helpers grow to a gigantic size,’ he explains, ‘then develop three more pairs of legs to become the ten-legged polar bears known as kiniq or qoqoqiaq.’

We don’t know much more than that about qupqugiaqs (most of those who survive an encounter only do so by killing the bear), although it would be wrong to think of them as malignant creatures just because they like to snack on human beings. That’s just bears being bears. Evidently the ten-legged polar bear can be an aid as well as a danger. In Explorations in Anthropology and Theology, by Frank A. Salamone and Walter R. Adams, the authors’ Inupiat host describes how his son inherited a ten-legged bear as an animal helper (a feral kind of guardian angel) from an ancestor. ‘Polar bear helpers grow to a gigantic size,’ he explains, ‘then develop three more pairs of legs to become the ten-legged polar bears known as kiniq or qoqoqiaq.’

There’s another kind of many-legged and nigh-on mythic bear out there, officialy named the tardigrade but more commonly referred to as the water bear. At less than a millimetre in size, it’s obviously not a member of the ursidae family of mammals. But, hey, those extra limbs also bar the ten-legged polar bear from entry into the mammalian club, so I’m calling both of these creatures as members of familus qupqugiaq. To make up for their size, water bears have powers. They can ressurect themselves, for a start, and they can become invulnerable when the need arises. In September 2007, two water bears blasted off in a rocket from Kazakhstan. In orbit around the Earth, they endured the airlessness and vastness of space as well as the lethal radiation of unfiltered sunlight. Then, after ten days, they returned from their mission alive and well. Here’s water bear expert Mike Shaw (no relation), outlining some of the amazing properties of these animals.

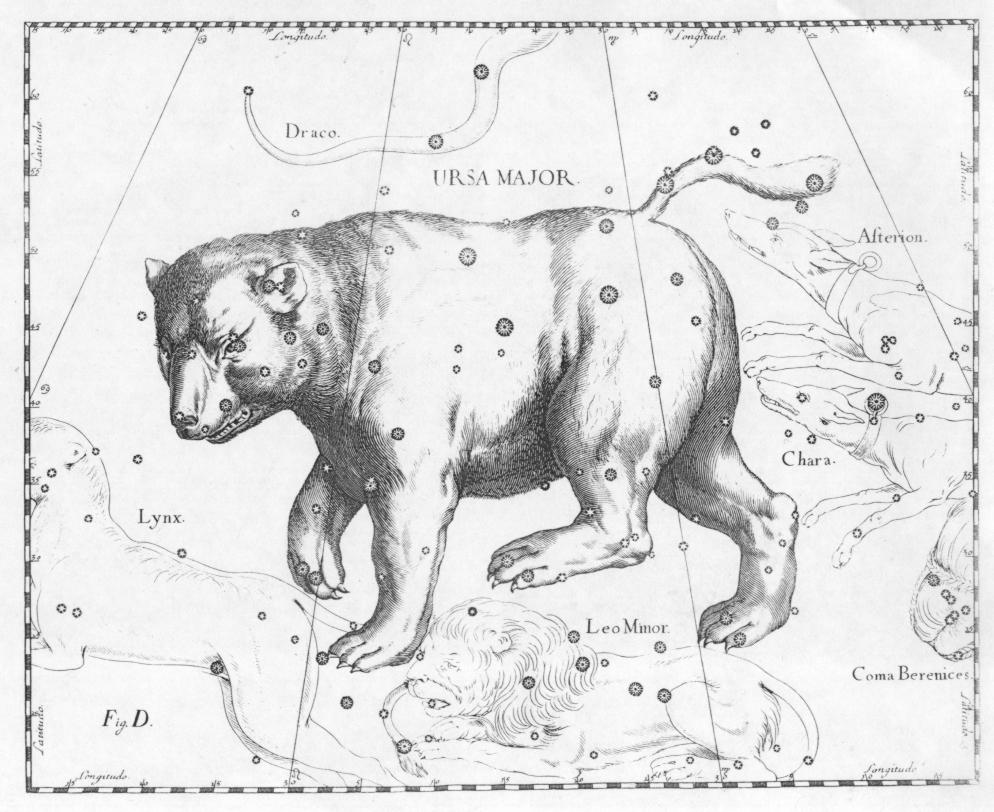

I can think of one reason why those water bears survived: there are already bears in space, and these star bears took a shining (forgive me) to them. Ovid describes how Juno transformed Callisto and her son Arcas into bears, only for Jupiter to throw them into space. You can listen to Ted Hughes read his translation of that sequence at the National Gallery’s website, and you really, really ought to. ‘Then to empty her cries of their appeal / The goddess nipped off her speech. Instead of words / A shattering snarl burst from her throat, a threat – / Callisto was a bear.’

I can think of one reason why those water bears survived: there are already bears in space, and these star bears took a shining (forgive me) to them. Ovid describes how Juno transformed Callisto and her son Arcas into bears, only for Jupiter to throw them into space. You can listen to Ted Hughes read his translation of that sequence at the National Gallery’s website, and you really, really ought to. ‘Then to empty her cries of their appeal / The goddess nipped off her speech. Instead of words / A shattering snarl burst from her throat, a threat – / Callisto was a bear.’

That story describes how the stars of Ursa Major came into being. Likewise the Iroquois tell a story of the same constellation bear. Three hunters chase the animal so high that they end up in the heavens. ‘As it broke from the cover of the pines, the four hunters saw it, a gigantic white shape, so pale as to appear almost naked. With loud hunting cries, they began to run after it. The great bear’s strides were long and it ran more swiftly than a deer.’ In outer space, they spear the bear, cook it and eat it. Then, to their amazement, it comes back to life. Like the water bear, it can withstand just about anything.

According to Wikipedia, ‘The pre-Christian Finns believed the bear to have come from the stars and that it had the ability to reincarnate.’ A chap called Matti Sarmela has written a fascinating and extensive study called The Bear in the Finnish Environment, where he notes that, ‘Narratives of the bear descended or evicted from heaven are also found with Siberian hunting peoples. One of the closest equivalents of the Finnish bear birth poem is the Khanty myth narrative. In the beginning of time, the bear lived in the heavens. Defying the orders of the master of heaven or supreme god To’rom, it wanted to take a peek at earth and was enchanted by the land of the Khanty. By defying the order, the bear committed a “deadly sin” and as punishment, the supreme god ordered that it should be lowered in a cradle by golden chains onto earth.’

According to Wikipedia, ‘The pre-Christian Finns believed the bear to have come from the stars and that it had the ability to reincarnate.’ A chap called Matti Sarmela has written a fascinating and extensive study called The Bear in the Finnish Environment, where he notes that, ‘Narratives of the bear descended or evicted from heaven are also found with Siberian hunting peoples. One of the closest equivalents of the Finnish bear birth poem is the Khanty myth narrative. In the beginning of time, the bear lived in the heavens. Defying the orders of the master of heaven or supreme god To’rom, it wanted to take a peek at earth and was enchanted by the land of the Khanty. By defying the order, the bear committed a “deadly sin” and as punishment, the supreme god ordered that it should be lowered in a cradle by golden chains onto earth.’

If interstellar cousins aren‘t behind the water bears’ miraculous antics, perhaps they’re due to all those legs. Perhaps many-legged bears are just plain magic. Further evidence comes in the form of one more nearly-bear, the woolly bear caterpillar. This is another diminutive species of qupqugiaq that likes to come back from the dead. It’s also my chance to once again shoehorn into this bestiary the work of the peerless David Attenborough. He, as far as I’m concerned, is the closest thing we have on Earth to a mighty bear spirit…