Sunk deep in the night. As one sometimes sinks one’s head in meditation, thus utterly to be sunk in the night. All around people are asleep. It’s a harmless affectation, an innocent self-deception, to suppose that they are sleeping in houses, in safe beds, under a safe roof, stretched out or curled up on mattresses, in sheets, under blankets; in reality they have gathered together as they once did of old, and again later, in a desert region, a camp in the open, a countless number of men, a host, a people, under a cold sky on cold earth, cast down where they had earlier stood, forehead pressed upon arm, face towards the ground, peacefully sleeping. And you are watching, are one of the watchmen, you find your nearest fellow by brandishing a burning stick from the brushwood pile beside you. Why are you watching? Someone must watch, it is said. Someone must be there.

– At Night by Franz Kafka, from The Great Wall of China and Other Short Works

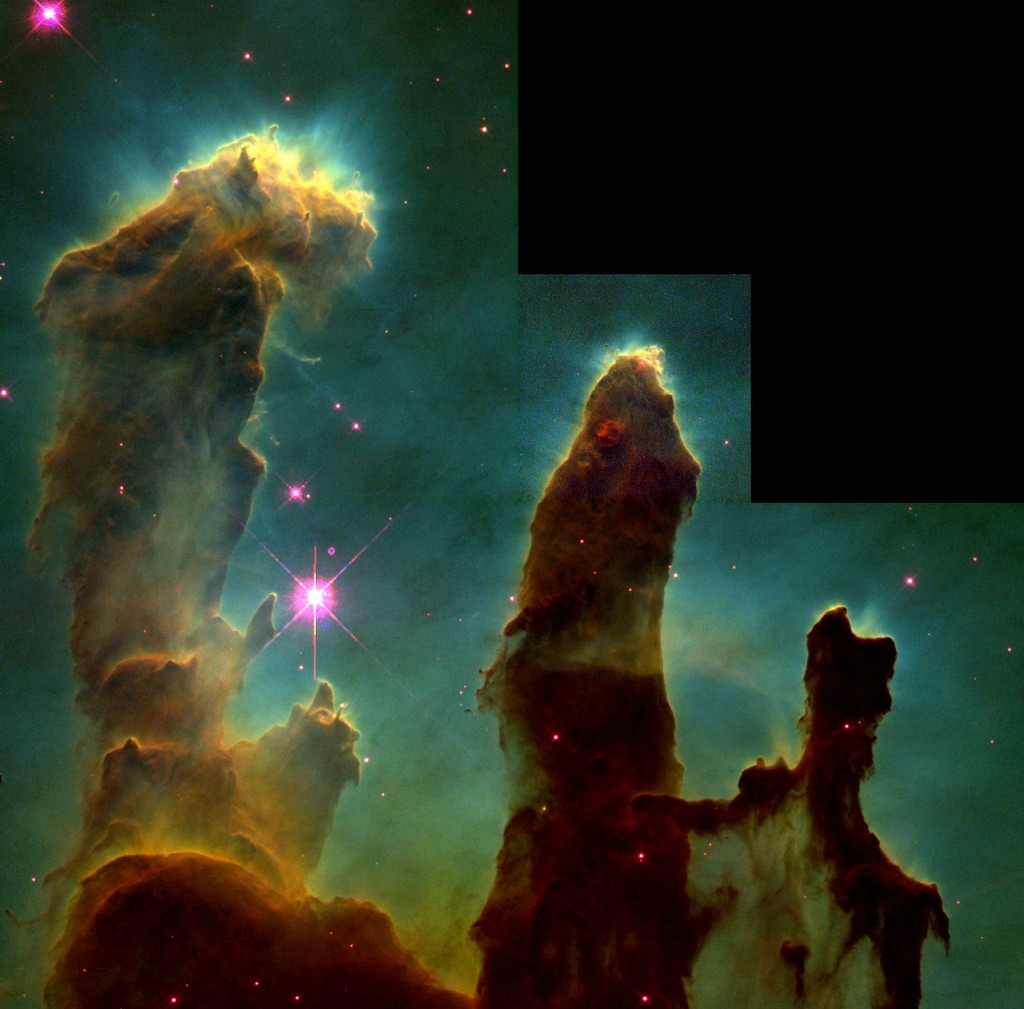

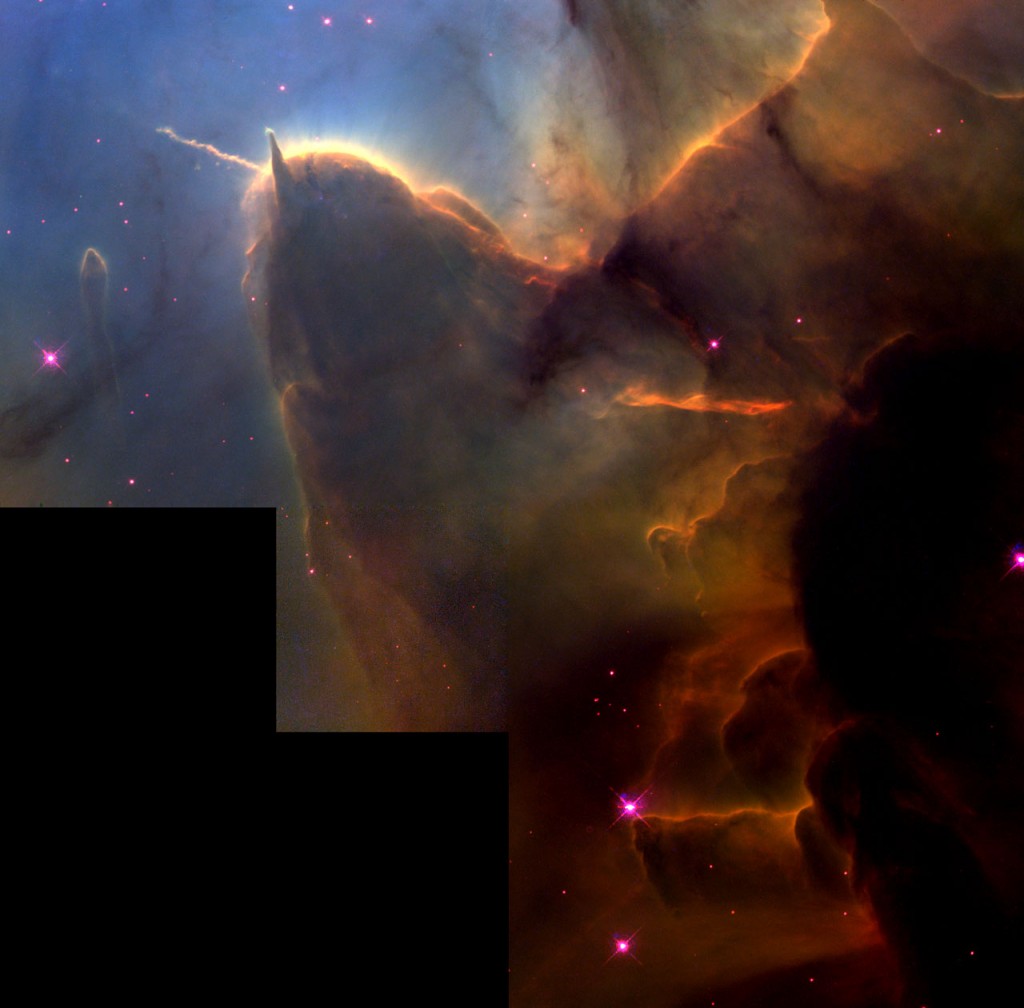

Scenes from a telescope/

The night planet electric/

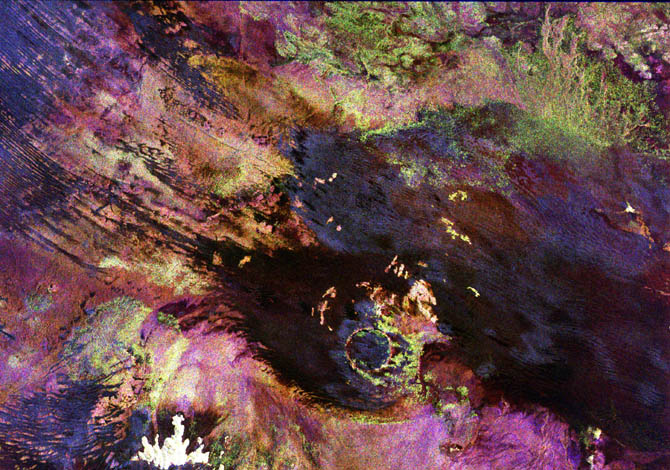

With all the trade routes of the world lit up/

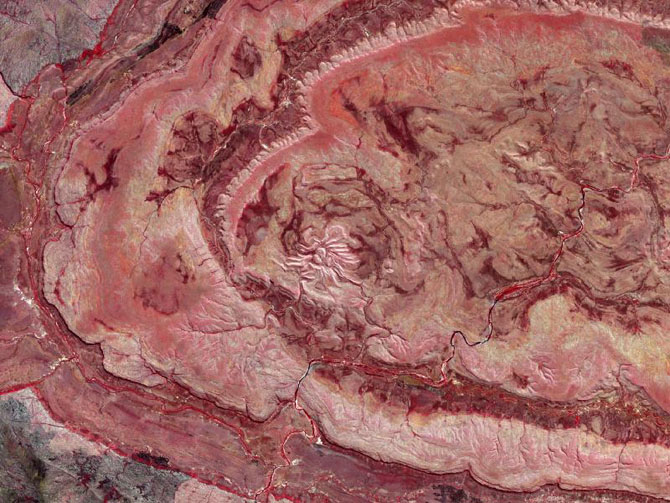

However, since nothing confutes the assumption that lines and forms and colours exist on innumerable other planets and suns as well, we are at liberty to feel fairly serene about the possibilities of painting in a better and different existence, an existence altered by a phenomenon that is perhaps no more ingenious and no more surprising than the transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly or of a grub into a maybug.

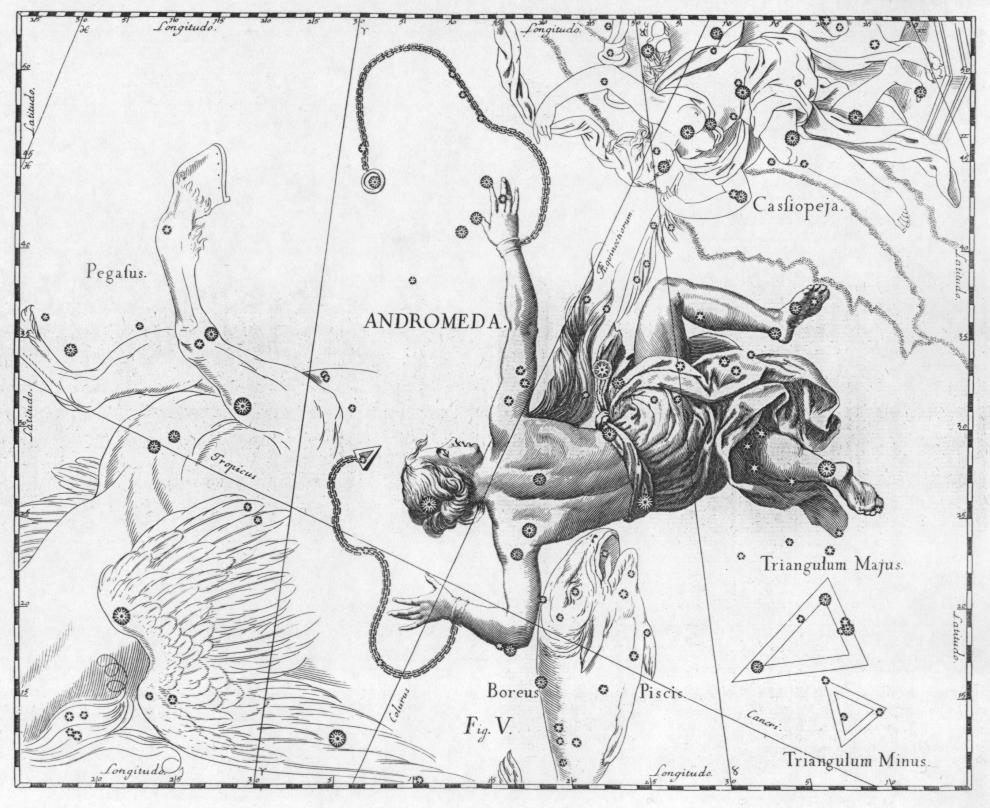

The existence of a painter-butterfly would be played out on the countless celestial bodies which, after death, should be no more inaccessible to us than the black dots on maps that symbolize towns and villages are in our earthly lives.

Science – scientific reasoning – strikes me as being an instrument that will go a very long way in the future.

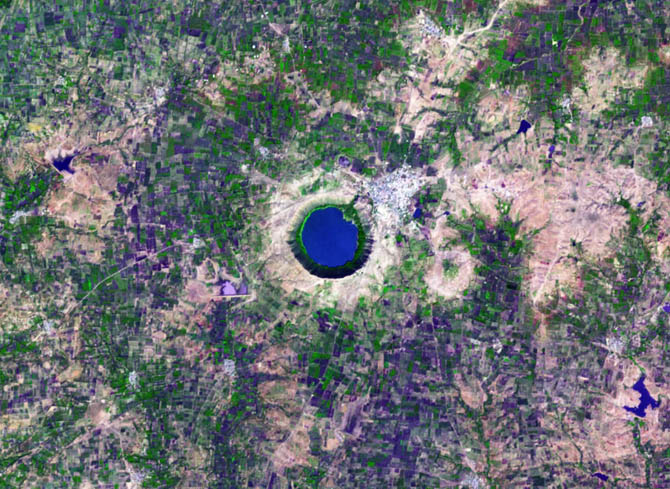

For look: people used to think that the earth was flat. That was true, and still is today, of, say, Paris to Asnières.

But that does not alter the fact that science demonstrates that the earth as a whole is round, something nobody nowadays disputes.

For all that, people still persist in thinking that life is flat and runs from birth to death.

But life, too, is probably round, and much greater in scope and possibilities than the hemisphere we know.

– Vincent van Gogh, from The Letters of Vincent van Gogh

Such science will go a very long way in the future/

Perhaps to the moon on a ladder of light/

And back in an all-too-brief freefall…/

Inevitably, what seems realest to us is what gets activated most often. Our hangnails are incredibly real to us (by coincidence, I found myself idly picking at a hangnail while I was reworking this paragraph), whereas to most of us, the English village of Nether Wallop and the high Himalayan country of Bhutan, not to mention the slowly swirling spiral galaxy in Andromeda, are considerably less real, even though our intellectual selves might wish to insist that since the latter are much bigger and longer-lasting than our hangnails, they ought therefore to be far realer to us than our hangnails are. We can say this to ourselves till we’re blue in the face, but few of us act as if we really believed it. A slight slippage of subterranean stone that obliterates 20,000 people in some far-off land, the ceaseless plundering of virgin jungles in the Amazon basin, a swarm of helpless stars being swallowed up one after another by a ravenous black hole, even an ongoing collision between two huge galaxies each of which contains a hundred billion stars – such colossal events are so abstract to someone like me that they can’t even touch the sense of urgency and importance, and thus the reality, of some measly little hangnail on my left hand’s pinky.

We are all egocentric, and what is realest to each of us, in the end, is ourself. The realest things of all are my knee, my nose, my anger, my hunger, my toothache, my sideache, my sadness, my joy, my love for math, my abstraction ceiling, and so forth. What all these things have in common, what binds them together, is the concept of “my”, which comes out of the concept of “I” or “me”, and therefore, although it is less concrete than a nose or even a toothache, this “I” thing is what ultimately seems to each of us to constitute the most solid rock of undeniability of all. Could it possibly be an illusion? Or if not a total illusion, could it possibly be less real and less solid than we think it is? Could an “I” be more like an elusive, receding, shimmering rainbow than like a tangible, heftable, transportable pot of gold?

– from I Am A Strange Loop by Douglas Hofstadter

…from a rock to a hard place.