She appeared to be a slight and graceful person, handsomely dressed; and her hair was arranged like that of a young girl of good family. ‘O-jochu,’ he exclaimed, approaching her, ‘O-jochu, do not cry like that! … Tell me what the trouble is; and if there be any way to help you I shall be glad to help you.’ (He really meant what he said; for he was a very kind man.) But she continued to weep – hiding her face from him with one of her long sleeves … Then that O-jochu turned around, and dropped her sleeve, and stroked her face with her hand – and the man saw that she had no eyes or nose or mouth.’

– from Mujina by Lafcadio Hearn

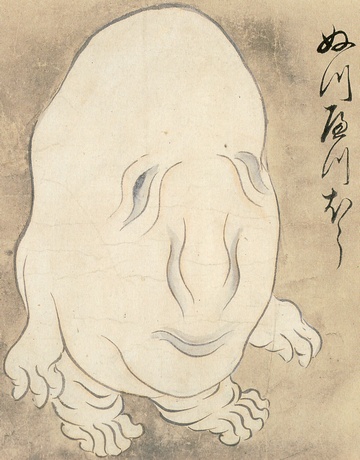

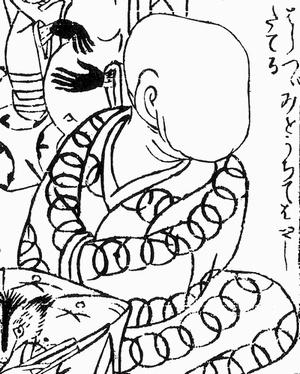

The only interesting thing about a monster is its humanity. When, in the back of a book of a thousand imaginary beings, I came upon a Japanese print labelled Noppera-bo, I was at once struck by its sense of sadness. It seemed like it carried a weight too heavy for a creature so small and shapeless. This noppera-bo was a strange, sagging creature with an arrangement of wrinkles in place of a face. I started reading what I could about it: that it was a ghost found weeping or in great distress. When comforted, it would turn to face the comforter then wipe a hand across its face. With that motion its features would smudge away: eyes, nose and lips smoothing out into a face as plain as eggshell.

The only interesting thing about a monster is its humanity. When, in the back of a book of a thousand imaginary beings, I came upon a Japanese print labelled Noppera-bo, I was at once struck by its sense of sadness. It seemed like it carried a weight too heavy for a creature so small and shapeless. This noppera-bo was a strange, sagging creature with an arrangement of wrinkles in place of a face. I started reading what I could about it: that it was a ghost found weeping or in great distress. When comforted, it would turn to face the comforter then wipe a hand across its face. With that motion its features would smudge away: eyes, nose and lips smoothing out into a face as plain as eggshell.

I loved this story but it didn’t seem to fit the wrinkled fellow in my print. Turns out that little guy is a nuppeppo, a different kind of ghost entirely, whom the compilers of my book had confused with the noppera-bo. There’s not a lot to be said about the nuppeppo, except that he smells of fetid meat and to eat him grants immortality. But I don’t think the world needs the sort of people who’d cook nuppeppos to live forever.

But what of the noppera-bo? Facelessness is a powerful idea. We’re hard-wired to hone in on human faces and pick them out in the most unlikely of places. There was a spot in 2011’s Royal Institute Christmas lectures in which Bruce Hood showed an eleven week old baby one abstract pattern and one pattern that resembled a human face. Immediately the baby attuned himself to the face (you can watch it here – fascinating from start to finish but the bit I mentioned starts at 7.20). Likewise we often imagine faces in clouds, bark or the burned surfaces of our toast. Since we’re so hyper-sensitive to the pattern of a human face, it follows that we’re unnerved on some deep-seated level if we focus on the place where a face should be and find it wiped away – find nothing there at all.

But what of the noppera-bo? Facelessness is a powerful idea. We’re hard-wired to hone in on human faces and pick them out in the most unlikely of places. There was a spot in 2011’s Royal Institute Christmas lectures in which Bruce Hood showed an eleven week old baby one abstract pattern and one pattern that resembled a human face. Immediately the baby attuned himself to the face (you can watch it here – fascinating from start to finish but the bit I mentioned starts at 7.20). Likewise we often imagine faces in clouds, bark or the burned surfaces of our toast. Since we’re so hyper-sensitive to the pattern of a human face, it follows that we’re unnerved on some deep-seated level if we focus on the place where a face should be and find it wiped away – find nothing there at all.

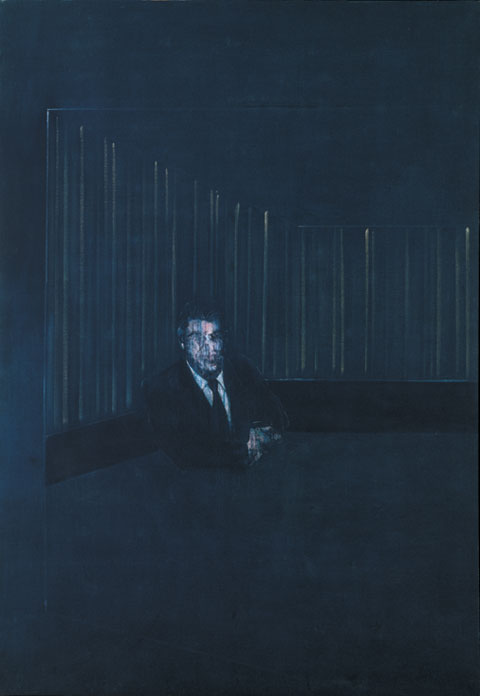

When I was a kid, my art hero was Francis Bacon. My noppera-bo pastel drawings at the top of this post are basically a rip-off of his style. Throughout his career, Bacon obscured, smudged and obliterated the faces of his subjects. In his Man in Blue series he painted anonymous businessmen whose eroded features contrasted unnervingly with the crisp precision of their suits. I think of them each in one of two ways, either as down-trodden workers with their identities sapped away, or as terrifying bureaucrats whose humanity has melted from them along with their faces. Therein lies the paradox of facelessness. When we use the word in general parlance we either talk about string-pulling elites in shadowy boardrooms or the voiceless masses forced into anonymity by poverty or oppressive systems. Certain sections of our society become vocally perturbed by balaclavas, hoodies, burqas, and so on, because they all prompt our gut fear of facelessness, of noppera-bos. But of course the weirdly beautiful thing about being human is that we’re often at our best when we act in contradiction of our animal impulses. When the noppera-bo is come upon weeping, are its tears really a trick to lure the unwary, or are they the genuine despair of a person made faceless in the powerless sense?

When I was a kid, my art hero was Francis Bacon. My noppera-bo pastel drawings at the top of this post are basically a rip-off of his style. Throughout his career, Bacon obscured, smudged and obliterated the faces of his subjects. In his Man in Blue series he painted anonymous businessmen whose eroded features contrasted unnervingly with the crisp precision of their suits. I think of them each in one of two ways, either as down-trodden workers with their identities sapped away, or as terrifying bureaucrats whose humanity has melted from them along with their faces. Therein lies the paradox of facelessness. When we use the word in general parlance we either talk about string-pulling elites in shadowy boardrooms or the voiceless masses forced into anonymity by poverty or oppressive systems. Certain sections of our society become vocally perturbed by balaclavas, hoodies, burqas, and so on, because they all prompt our gut fear of facelessness, of noppera-bos. But of course the weirdly beautiful thing about being human is that we’re often at our best when we act in contradiction of our animal impulses. When the noppera-bo is come upon weeping, are its tears really a trick to lure the unwary, or are they the genuine despair of a person made faceless in the powerless sense?

Just as we can be unnerved by facelessness, we can be moved by it. If the men and women who this old B-movie takes for its inspiration evoke any kind of horror it’s the horror of their fate. The plaster casts of Mount Vesuvius’ incinerated victims still speak their horror, some one thousand nine hundred and thirty three years since their mummification in ash. Their faces are barely more detailed than that of the noppera-bo. Anonymous victims, but it takes only an inflexion in plaster for them to haunt us still.

Just as we can be unnerved by facelessness, we can be moved by it. If the men and women who this old B-movie takes for its inspiration evoke any kind of horror it’s the horror of their fate. The plaster casts of Mount Vesuvius’ incinerated victims still speak their horror, some one thousand nine hundred and thirty three years since their mummification in ash. Their faces are barely more detailed than that of the noppera-bo. Anonymous victims, but it takes only an inflexion in plaster for them to haunt us still.

In Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 maserpiece Spirited Away, a girl becomes lost in a world of monsters, many of them faceless or masked. She’s imprisoned in a bewitched bath-house by a sorceress who steals her name. But our heroine, Chihiro, learns much about herself by having her identity stripped from her. One of the ghosts in the film is called No-Face, a shapeless figure of black wearing an egg-shell smooth mask. No-Face is introduced as a frightening monster, munching on the hotel staff, but come the latter stages of the film it has befriended Chihiro and become a lonely, reflective figure.

Spirited Away is all about stolen identities. Until she recaptures her name from the sorceress, Chihiro cannot know who she was before coming to the bath-house. She’s in a nightmarish predicament, but here’s the catch. It’s through losing her identity that she learns about herself. Perhaps facelessness can mean a liberation?

As well as being hard-wired to fear facelessness, we’re also equipped with astonishing powers of face recognition and empathy. Our instinctive empathy enables us to feel some part of what another person’s face is expressing, even if that face is incomplete or only partially human. Hence our ability to cry at cartoon lions or sympathise with the plaster-cast victims of Vesuvius. This next is conjecture, but I suspect a similar part of our brain is active when presented with a story. We can empathise with the mental images created with words. We can empathise with a wordless human song or cry.

As well as being hard-wired to fear facelessness, we’re also equipped with astonishing powers of face recognition and empathy. Our instinctive empathy enables us to feel some part of what another person’s face is expressing, even if that face is incomplete or only partially human. Hence our ability to cry at cartoon lions or sympathise with the plaster-cast victims of Vesuvius. This next is conjecture, but I suspect a similar part of our brain is active when presented with a story. We can empathise with the mental images created with words. We can empathise with a wordless human song or cry.

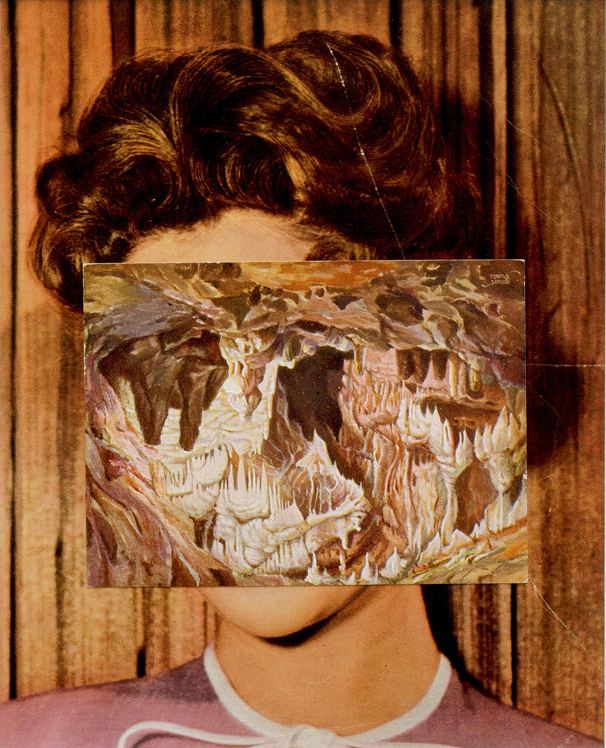

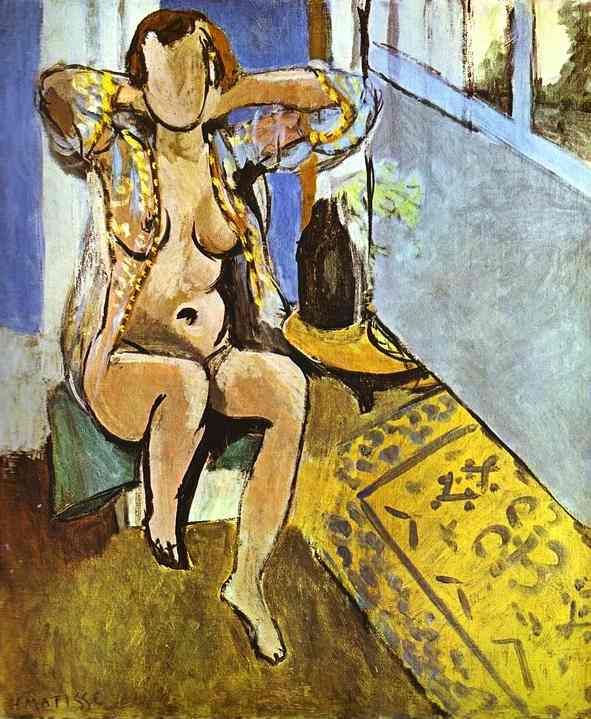

Wiped-blank faces encourage us to reach elsewhere with our empathy. T0 the right is one of Henri Matisse’s occasional faceless figures, Nude, Spanish Carpet. It hardly evokes the dread of Francis Bacon’s tortured souls. And below are some of John Stezaker’s amazing collages of old photos mashed with landscapes, from his series Masks. Here facelessness is striking, but it doesn’t terrify. For my part it makes me think of worlds within, deep rich realms waiting to be explored.

Characters in fairy stories very rarely have their histories fleshed out. Often they are attributed with only the most basic of personalities and described in the broadest terms possible (they might not even get as far as being ‘beautiful’ or ‘ugly’ or ‘golden-locked’). Names, too, are not regularly used, unless they’re the same name over and over like Hans or Jack. Instead of being asked to view such characters as distinct from ourselves, we’re encouraged to see them as everymen, almost as a kind of bait for our empathy to leap on. I’m sure we’ve all speculated, at some point in our lives, about what it would be like to disappear completely and reinvent ourselves in some far-flung corner of the world, but in stories we are doing this all of the time. And in the moments of transition, when we are becoming ‘lost’ in a good book or film, perhaps we are noppera-bos, wiping off our regular faces in order to experience life behind another.