On a chill autumn night a beggar woman brought a boy kicking and screaming into the world. The beggar knew from bitter experience that a winter spent in icy gutters and crowded almshouses meant death for an infant. She remembered all too well the blue lips and frozen digits of her firstborn, whom she had lowered into the earth.

So it was with a heavy heart that she set off into the woods, as soon as the baby was strong enough to withstand the journey. Leaves fell about her like a flaky brown snow. Damp loam oozed its moisture through the splits in her ragtag boots. The forest seemed to crave the winter. The earth had frozen prematurely underfoot. She scrambled along what paths and animal tracks she could discern, and just as she was beginning to think that she was hopelessly lost, she emerged into a glade.

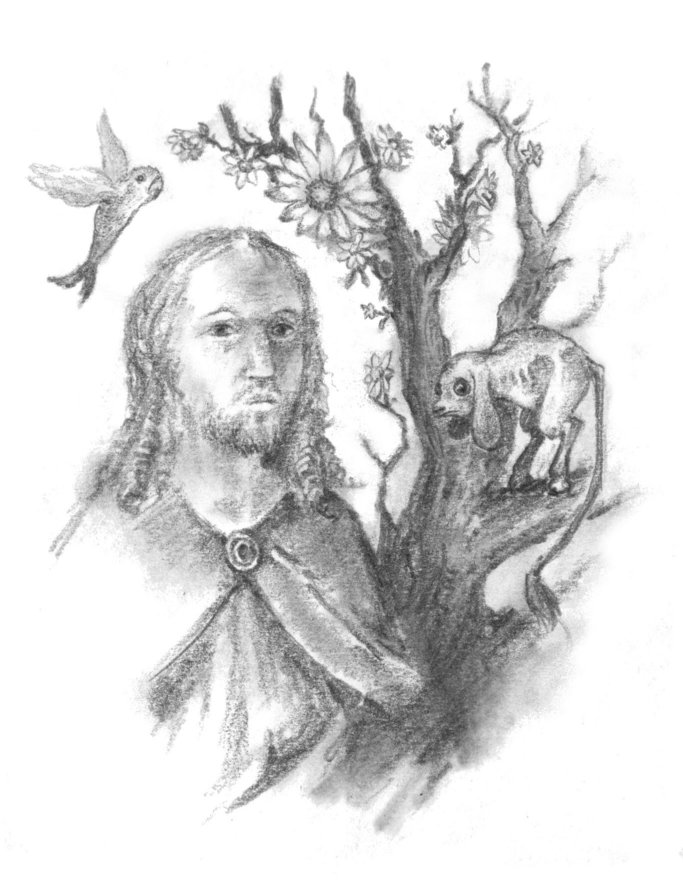

Here the leaves looked greener and firmer. Blossoms still lit up the branches and made the air sweet-scented. In this one circle of trees, at least, autumn clung tenaciously to the summer.

Here the leaves looked greener and firmer. Blossoms still lit up the branches and made the air sweet-scented. In this one circle of trees, at least, autumn clung tenaciously to the summer.

In the centre of the glade stood a solemn young man with a face world-weary beyond his years. His clothes shimmered like sunlight off of rippling water and he was surrounded by all manner of fabulous creatures, the species of which the beggar could not name. The man looked up at the beggar and the baby in her arms and asked in tones of faint sadness, ‘What are you doing here, lost in the woods?’

‘I’m looking for a godfather to take and raise my son.’

This seemed to bring the first turnings of a smile to his lips. ‘I will do it.’

‘Then tell me your name.’

‘Do you not know me? I am the Lord of Heaven.’

Alarmed, the beggar backed away. She gripped her baby tight. ‘Oh no, then you’ll never do for a godfather. For you are not just. You let the weak and needy suffer while the strong and rich feast and dance.’ And with that she fled from the blossoming glade, and all at once the chill evening caught her breath and the woods seemed dark and full of the eerie hoots and gruff calls of hidden beasts.

After wandering lost for a while more, the beggar stumbled upon a second glade. Here the boughs of an ancient briar parted and rose like the arms and base of a throne, and on this arboreal seat perched the most peculiar of monsters, licking rank meat from the tips of its talons. From the twisted branches around it misshapen creatures leaned, whispering sibilant advice to the monster.

It fixed the beggar with its beady eyes. ‘What are you doing here, lost in the woods?’

It fixed the beggar with its beady eyes. ‘What are you doing here, lost in the woods?’

‘I’m looking for a godfather to take and raise my son.’

The monster clapped its hands in a clatter of talons. ‘Ooh,’ it trilled, ‘I will do it.’

‘Then first tell me your name.’

‘Do you not know me? I am the Prince of Hell.’

The beggar covered her newborn’s eyes. ‘Oh, I know you, Mister! And you shan’t have him, for you are not just. You damn those who serve you just like the damned who don’t.’

And with that she fled the glade, and the forest seemed now welcoming and warm and full of gruff sounds and woodsy smells all reassuringly earthy.

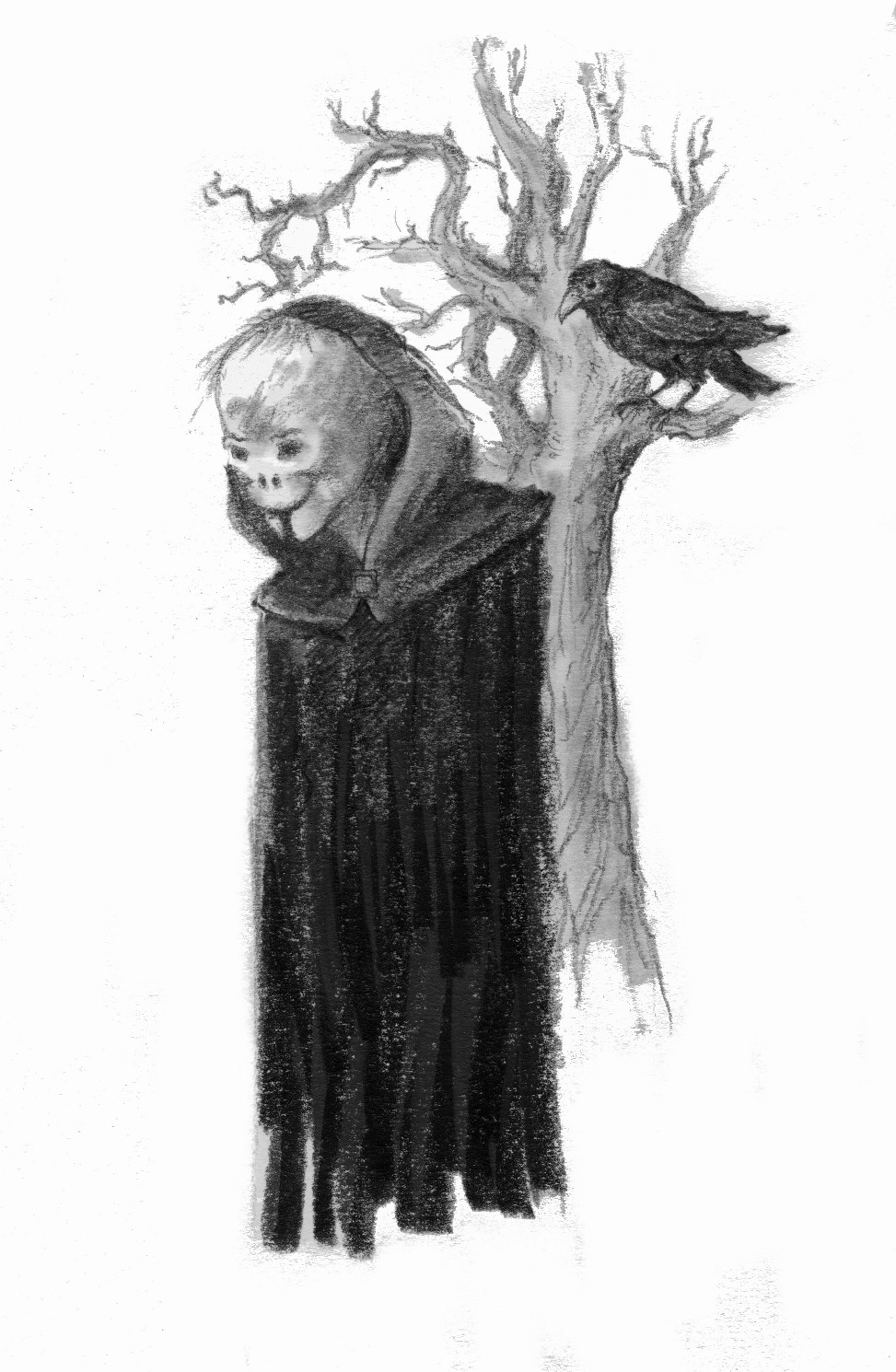

After wandering lost for a while more, the beggar chanced upon a third glade. Here, in an old deckchair, a wizened figure reclined, snoring into a book of limericks he had been reading.

A twig cracked under the beggar’s tatty boots and the stranger woke with a start. Then he composed himself, marked his page with a bookmark fashioned from a carrion crow’s feather, and smiled. The beggar stifled a scream, because the skin of the stranger’s face was stretched as thinly and tightly across his skull as the skin of a drum, and the fingers that poked from the sleeves of his black robe were wire thin and ivory-hued.

‘Before you ask what I’m doing,’ said the beggar, ‘lost here in the woods, I venture to say that I know who you are.’

The stranger stood up straight and tall. His robe hung emptily from his shoulders like a curtain from a rail.

‘You’re Death,’ pronounced the beggar.

‘Correct, my dear woman. And you are?’

‘I’m nobody. But I hope that this boy will grow up to be somebody. So I’m looking for a godfather to take and raise him.’

And Godfather Death did just that, carrying the infant home to his halls. There he raised him and taught him the secret signs that warned of his own impending visits, and among them was this one: that the boy could always tell whether or not a sick patient was doomed to die by watching for Death’s shadow at the deathbed. If his shadow loomed at the foot of the bed, death was inescapable. If the shadow darkened the head, death was for another day.

Armed with this and other insider knowledge, the boy grew up to be an exemplary physician. Such was his skill that he spent his days travelling the continent, called from home to home to cure the sick or else ease the passing of the suffering.

Then one day a great emperor fell ill and summoned the physician. He rode hell for leather to the emperor’s court, where he found him shrivelled and needy in the royal bed. The physician turned grave-faced, for as he examined the emperor he became gradually aware of a column of shadow at the foot of the bed. This apparition was the sign his godfather had warned him of, and it meant the emperor’s demise was imminent.

Then an idea struck him. He called for the butler, the cook and the doorman, and together they turned the bed around one hundred and eighty degrees. The physician took a seat and waited for his godfather to arrive.

He was not long in coming. He materialised in a cloud of smoke, smelling of cloves and pipeweed. The physician stood up and greeted him heartily. ‘But, my dear godfather, there must be some mistake. Look where you’re standing, at the foot of the bed. By your own law this means the emperor will survive. Why don’t you go back to your halls and enjoy a fine glass of chilled wine?’

Godfather Death stood as silent as a stone, which lies at the bottom of a well in a forgotten town. Then, in the blink of an eye, he vanished.

The emperor spluttered and a healthy pink blushed through his cheeks. In a week he was walking, and in a week and a half he was throwing a feast in honour of the physician, who became the toast of the entire empire. At the feast the physician talked and danced the night away with the emperor’s only daughter, and at the end of the night he and the princess slipped away to a quiet room at the end of a quiet corridor, and there they were very happy.

But… Godfather Death had seen through his adopted son’s deception. And he was seething, for he would not be cheated.

The next morning before the cock crowed the physician woke to a bony grip around his wrist. It was his godfather, whispering, ‘Because you are like a son to me I will forgive you this one insult, but if you ever try to dupe me again your life will be forfeit.’

Days passed. Weeks, months. The physician and the princess became engaged, and at the wedding party the physician’s godfather drank too much wine and hitched his robes up and jigged merrily with the bride. It seemed as if all was forgiven.

A year later the princess was pregnant. Nine months after that a baby girl squealed into the world, plump and a picture of health. Yet after the birth the princess fell ill. Her labour had not been straightforward. The physician tended to his bride day and night, forgetting to eat or drink as he administered her medicines and mopped her feverish brow. Then one night, rising from her bedside and rubbing his tired eyes, he beheld a column of shadow stretching from the foot of her bed to the ceiling. He vomited. His heartbeat went crazy. He called out to the shadow. He tried to reason with it. But it faded and the warning had gone.

He sat with his head in his hands. He chewed his fingernails until he drew blood. Then abruptly he rose and called to the butler, the cook and the doorman. Together they turned the bed one hundred and eighty degrees, and by the time the morning came the princess’s sleep was less fitful and her colour had returned. Then Godfather Death appeared.

The physician declared, with a sweet-as-you-please performance, that this was an unexpected pleasure. ‘How good of you, Godfather, to pay us a visit at this troubling time. But as you can see by the evidence of your own law, my wife is destined to make the fullest of recoveries.’

Death looked down at the foot of the bed and at the bulge of the princess’s feet beneath the quilts. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I see that now. She is going to live. But please… spare your old godfather a quiet word outside.’

Death wrapped a bony arm around his godson’s shoulders and together they ambled out of the door. But to the physician’s shock it did not lead, as it had on every previous exit, to the palace corridor. Instead he and his godfather stepped through it into a vast and freezing cavern. Behind them the door vanished and there was only the cavern stretching as far as the eye could see. The air was silent and still, and that suited this underworld well, for here in their billions candles burned. Some were elegant and tall, rising from the stone floor like flaming stalagmites, others were burnt down to sputtering stumps.

‘Where are we, Godfather?’

‘We are in the Cave of Candles, where wick and tallow flicker for every human life on Earth.’

‘Some of these candles are taller than others.’

‘Some lives have shorter time to burn.’

‘And what happens when a candle, such as this one–’ here he pointed to the nearest, which had melted almost as flat as a coin, and where the flame trembled its last in a circle of shiny wax ‘–has burned so low that any second now it will snuff out.’

‘It snuffs out,’ said Godfather Death, and at that precise moment the candle’s light winked out and the physician fell down dead on the stone.