Ever since he was a pup, he had felt the stars tugging at the heart of him as if their distance only amplified their gravity. Many a vole or cottontail had been spared the final lethal snapping of his fangs when, distracted at the last by a glint seen out of the corner of his eye, he had turned his attention upwards and stood rapt, with his legs stiff and his jaw hanging open and his ears pressed flat against the fur of his neck, staring into the sparkling cosmos and feeling once again its pull on the core of his being. It was a pull so hard to forget, like remorse.

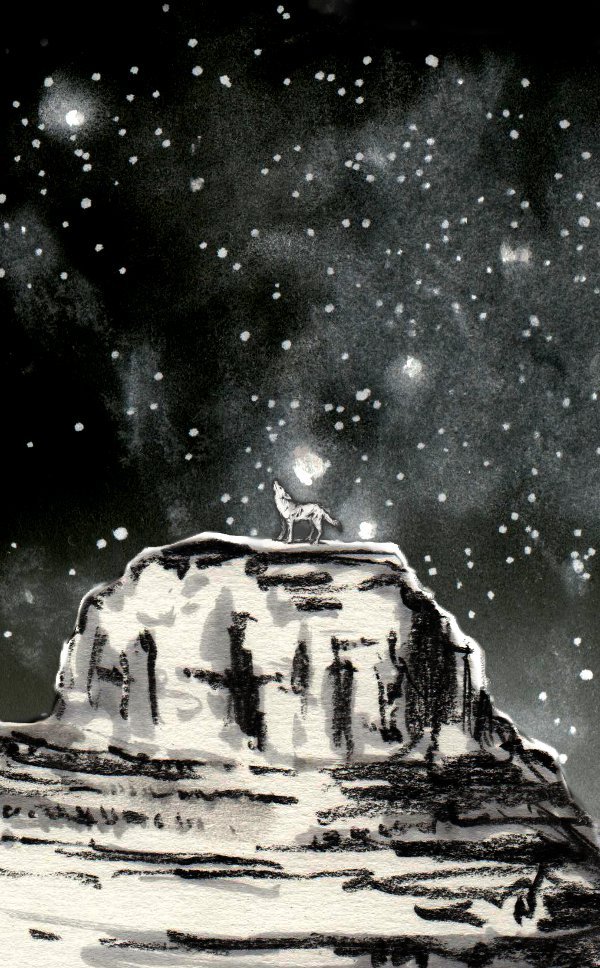

Out in the desert loomed a mesa of pale stone, taller than any in a hundred miles. One midnight, when disturbed from luxuriant dreams of carrion by the tiptoe in his nostril of a horsefly, he opened his eyes and thought he saw the stars dancing. They swept low over the mountain, then up in graceful arcs, weaving around each other in the blue night. Sweet dreams tempted his eyelids shut and he drifted back to sleep. But in the morning he awoke with a burning desire to dance among stars.

Out in the desert loomed a mesa of pale stone, taller than any in a hundred miles. One midnight, when disturbed from luxuriant dreams of carrion by the tiptoe in his nostril of a horsefly, he opened his eyes and thought he saw the stars dancing. They swept low over the mountain, then up in graceful arcs, weaving around each other in the blue night. Sweet dreams tempted his eyelids shut and he drifted back to sleep. But in the morning he awoke with a burning desire to dance among stars.

It took him the day to scrabble up the mesa, putting his agility to the test on steep and narrow paths. Come dusk he was trotting over the flat summit, impatient for the stars to descend and include him in their night ballet. When the first glimmer broke through, he yapped and howled to demand its attention. He did not know whether it had heard him, but as it descended he had to shield his eyes with a paw, for it grew from a speck to a colossal creature whose brightness veiled its form. Even through his squeezed-shut eyelids it was blinding, too brilliant for any shadow or blemish to convey its shape. Its light was a cold light, as cold as the night in these deserts, and when he leapt with limbs outstretched and caught a grip on its underside, and sank his claws in and his teeth too, he could detect no warm blood pulsing under its dazzling hide.

The star’s pendulous momentum soon sent it soaring upwards. He could tell from the rippling of his fur and his tail streaming out behind him that they were accelerating to blurred speed. As they ascended through the atmosphere the star’s light seemed to dim. It was as if the darkness of space were more resplendent still, and what had seemed on earth to be unquenchable brightness became but a candle flame clinging to a wick. He had to summon all his courage to gaze out into that pitch silence, and he thought that the far-off swimming glints of other stars were not truly in the distance, but that the distance was the black engulfing them and the black was the true face of the universe. He barked that this was enough, enough, enough, but the star soared onwards, and although it passed planets of marbled gas and comets leaving crystalline blue trails in their wakes, he wanted only the dirt between his toes and the hard enclosing walls of his den.

He clung on. There was no dawn or red sunset to measure the hours by, no new shoots, no tasty skipping newborns in the fields, no long shadows, no dropping of the last leaves from the twigs, but he felt that he grew old there hanging from that star, and that he had time to grow old a second time before its journey brought it back towards the blue planet of his birth. His eyes welled up when he saw it, for in that emptiness it looked as inadequate and perfectly formed as a bubble. His tears strung out behind him in the star’s wake. A trail of watery orbs floating in the void, as if a tribute to his home sphere. Fearful that the star would blaze on past the Earth and not return for a millennia, he again plucked up courage. He let go. The star shot onwards into nothing and he fell, reeled in, tumbling into the atmosphere, through air thickening with clouds, past startled condors and high-flying insects, his fur singing from the speed of his plummet, until he crashed hard into the unforgiving rock he had so sorely missed.

He clung on. There was no dawn or red sunset to measure the hours by, no new shoots, no tasty skipping newborns in the fields, no long shadows, no dropping of the last leaves from the twigs, but he felt that he grew old there hanging from that star, and that he had time to grow old a second time before its journey brought it back towards the blue planet of his birth. His eyes welled up when he saw it, for in that emptiness it looked as inadequate and perfectly formed as a bubble. His tears strung out behind him in the star’s wake. A trail of watery orbs floating in the void, as if a tribute to his home sphere. Fearful that the star would blaze on past the Earth and not return for a millennia, he again plucked up courage. He let go. The star shot onwards into nothing and he fell, reeled in, tumbling into the atmosphere, through air thickening with clouds, past startled condors and high-flying insects, his fur singing from the speed of his plummet, until he crashed hard into the unforgiving rock he had so sorely missed.

He lay there for some days, as dead as the stone beneath him, the wind ruffling his coat, the sunshine drying out his upturned eyes. There the Great Mystery Power found him and poked him back to life.

At once he missed it. Not the coloured glares of alien atmospheres, nor the ribbons of asteroid belts or the thumb prints of spiral galaxies. He did not understand why, but he missed the black empty, of which this barren desert was but a poor imitation. He looked up at the Great Mystery Power and implored it with puppy eyes to let him fly once again with the stars. ‘Friend Coyote,’ it whispered, ‘I have given you four lives, the first of which you have wasted. Do not chase the loss of the second.’

He accepted this begrudgingly. He was distracted by a ground squirrel springing over rocks, at which his reborn stomach growled back into life. He wondered how long it had been since last he had eaten. It might have been years. He lunged after the ground squirrel, and the Great Mystery Power chuckled and tiptoed on its way.

He could not sleep that night. He watched the stars, framed by the opening of his den, dancing above the mesa on the horizon. There were a great many of them circling there, but now he watched only the space in between, the dark eternity out of which they had travelled. By the time the sun came up he was already halfway to the mountain, and by the time it went down he was pacing excitedly back and forth across the summit.

The stars that danced that night were smaller than his first. They moved in supple, swerving motions, like a pod of orcas playing in the wide ocean. He speculated that they were younger stars, immature and full of adrenaline. This made them harder to catch. He sprung as high as he could to try to grab hold of them, but each time he tried his jaws closed empty and his paws flailed after only a trail of light. Try as he might, he could not lay a claw on one. He hopped about in circles and yowled with frustration. Then, just as the stars headed skywards, to take their dance back up into space, the last of them dipped and seized him in its jaws. He squealed and kicked about but there was nothing he could do. The pod of stars rocketed heavenwards, and he felt again the rush of the atmosphere plunging away from him, and then he was shooting past the cratered moon, and then blazing onward into the mystifying black. Pain distracted him from the spectacles of the universe, as the star’s jaws tightened and he felt its teeth piercing his flank and his blood oozing out of him. When the star tried to adjust its grip he fought all-or-nothing to break free, and scratched and kicked his way clear for a brief moment before the star snapped him back up, then rent him open with one great bite, gnashed and tossed him about and tore strips from him, until he was ripped to pieces by its frenzy.

Meanwhile, in the desert, the Great Mystery Power was contemplating a tree stripped bare by locusts. It had been contemplating this for some time, but became distracted by an object falling from the sky near the mesa. Something else fell a little nearer by, then something more, each streaking to the ground with the struck-match spark of debris burning in the atmosphere. With an expectant sigh, the Great Mystery set off, and found lying in a tiny crater a yellowed canine tooth. The Great Mystery wandered the desert, finding here an ear, there a whisker, and there a scrap of scraggly fur. When it had gathered all the fallen pieces it laid them out in the dust, piecing them together with an artisan’s knack. ‘Friend Coyote,’ it whispered. ‘I have given you four lives and you have wasted two.’

He came alive with a splutter, the pieces of him fusing into one bruised and bedraggled whole. But when he tried to stand up he collapsed forwards, for his right front paw was missing entirely. He looked around in a panic. He sniffed the wind, but could smell no whiff of himself anywhere but here.

‘It is in the star’s belly,’ shrugged the Great Mystery. ‘Where I suppose it shall remain until the star coughs it up in the depths of space, or, if you are fortunate, when it next dances near the Earth.’

He whimpered, and squinted up at the opaque sky.

‘Don’t waste any more of your lives waiting on it,’ advised the Great Mystery. ‘Because although that star might return tomorrow, it might not return in a million years.’

And he howled then at the Great Mystery and felt as if the heart of him and not the paw were still up there, flying on unknown circuits through that interstellar nothing.

I really enjoyed your version of the story, thank you for putting it up. Your illustrations are beautiful and the galaxy is stunning (and only a little smoke is trickling from my screen…).

Reading this was the most charming part of Friday morning. Love the illustrations. Looking forward to The Man Who Rained!

I really enjoyed reading your version of the story, it was very good, but I think the drawing of the galaxy was wonderful.

I’m doing an art exam piece, the theme of which is glass (coincidental I know). I’ve been experimenting with a lot of different media and techniques and I was wondering, since I find your drawings so unique and interesting, if you could recommend an artistic media or technique which you like. If you could I’d really appreciate your opinion. thanks (:

Hey Summer, and good luck in advance with the art exam (although I’m sure you won’t need luck). Graphite sticks and smudgers are where it’s at, for me. There’s probably a technical name for smudgers, but I mean a kind of cottony/paper stick with a sharp end shaped like a pencil’s. You’ll find them next to the graphite sticks in most art shops. The great thing about them is that they can spread an even midtone and pick up less of the texture of the paper than, say, a pencil being used very lightly. They’re an easy way to get more grey areas among the sometimes too-stark blacks and whites of pencil drawing.

I tend to draw with graphite first, then smudge, then add or pick out detail with a sharp 5B. I also use the occasional bit of chalk or oil pastel. I used quite a bit of pastel on the stars in the Coyote story because I was drawing them as negative images (so it was useful to be able to overlay shadow using a white pastel). In doing that I discovered that using a very hard pencil like a 9H on an area of dense pastel is great fun – it’s like scraping around in mud on a very very tiny scale.

I appreciate that you’re probably getting more than you wanted here (I am a ridiculous person who can happily talk about pencils all day), but one last thing I enjoy is a very pale grey brush pen used along with charcoal. That’s how I did all of the pictures of Coyote. If you draw with the brush pen first you get a very faint but crisp image, which the inevitably scruffy charcoal complements.

Hope this is of some use. I’m off to hang out with my graphite some more…

The brush pen sounds good to me for a sharper definition. I think your “smudgers” mean tortillons or blending stumps, which sounds quite appealing as well. With the graphite, hopefully that can give me the smother transition in tones that I’ve been looking for (I mean shading pencils can only take you so far). Some really interesting options, thanks a lot this really helped. You enjoy your time with your graphite, I hope there are plenty more pictures on the way. Now all I have to do is find a half decent art shop somewhere in post-revolution Egypt. That should be an interesting endeavor 😀 .Thanks again.

p.s can’t wait to read the man who rained (: